This post started out as a quick Q&A piece designed to answer the question: what is micropublishing and why should I care about it?

The trouble began when I tried to define it much the way that I might have about seven years ago.

If this were 2005, I’d have said the following:

In many ways, micropublishing works just like conventional publishing business, except it’s a much smaller company doing the printing, done in reduced volume, for a much smaller market.

I can’t entirely stand by that definition anymore. There are a few reasons for that.

To understand micropublishing today, you still have to describe it relative to publishing. So let’s start there.

What does publishing mean anymore, anyway?

Our conventional understanding of what constitutes “publishing” has changed. It had to.

Every industry offers a product or service that solves a problem.

Publishing as an industry no longer solves the problems that it used to.

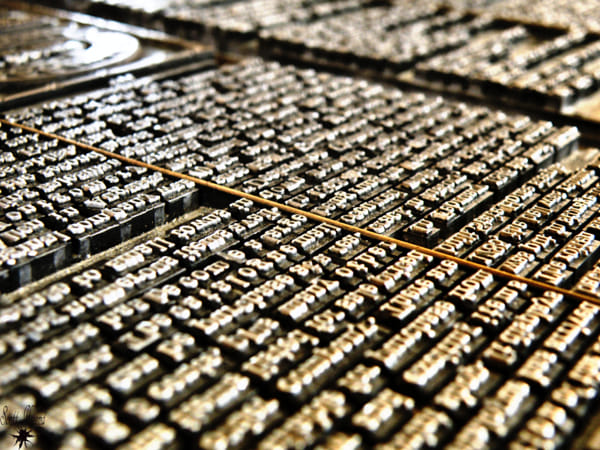

It used to be the only game in town for choosing a select bunch of good ideas from many bad ones and getting those ideas (usually the good ones) in the hands of many people. Printing was the large-scale industrial process it used to achieve that.

There was a marketing component, too. But the jury’s still out on how effective they’ve been in that department for the past decade or so.

Two big disrupters

None of this is meant to denigrate the work of industry publishers today. There are some very smart people in that business who do (and will continue to do) great work. They just happen to be on the receiving end of not one but two of the biggest disruptive ideas in the history of human communication.

First, the rise of online media. Publishing is a moveable idea now. It’s not just about books and newspapers anymore. In fact, on the scale of who is engaged in the act of publishing today, it has very little to do with books and newspapers anymore.

We are all publishers now. Not just in the sense that we each can publish our ideas on the web though blogs and social media. Publishing now is an act: not an industry.

I like how Seth Godin looks at this interesting problem. Publishing, he says, has “everything to do with creating a platform that enables ideas to spread.”

Ebooks are the second disrupter. And it’s astonishing how quickly they’ve hollowed out a centuries-old industry. Granted, they’re not a substitute for the feel of a paper book in your hands. But they solve a very important problem.

Because of the rise of ebook self-publishing as a platform, the time it takes to create and ship a product to market is now measured in days, not months or years under the old way of doing things.

Ebooks also have some unique advantages in terms of pricing. I’ll come back to that in an upcoming post.

Back to my problem with micropublishing

So where does that leave micropublishing? Good question. I still don’t really know how to define it anymore.

It’s still mostly a printing enterprise. It’s still all about being able to print in limited volumes if you want.

The trouble starts when you look at who is doing the printing and the size of the market for the work that’s done there.

When you can write a book or an annual report, design it, upload it to Amazon, distribute it electronically to readers worldwide, plus order and ship a select number of print versions of your book—however many or however few you want—it suggests that micropublishing is an idea that’s suddenly a lot more fluid than it used to be.

There’s not much that’s micro about it. If anything, it’s starting to look a lot more like just-in-time printing.

Publishing has become an idea that has outgrown the industry that created it. Micropublishing (whatever that’s supposed to mean anymore) has helped that along and has also been reshaped in the process.

What’s left and what’s ahead

Distribution is the last freestanding wall controlled by traditional publishing. It’s going to get really interesting when it falls soon.

It’s what’s holding back many entrepreneurs, professional speakers, authors, poets from leaving the traditional publishing model, because they’re looking to sell hard-copy books in high volumes and up until now, publishers still corner that market.

Even prolific fiction writers—people like Dean Wesley Smith, for example—who’ve embraced the new way of doing things make a point of noting that this is still new…even for them. “Traditional publishing,” says Smith, “was still the only real choice just two short years ago.”

Change is coming.

You don’t have to look too hard at the industry to see that it’s only a matter of time. Writer and technology thinker Clay Shirky predicts it might only be a matter of a few years before major booksellers start saying “We can’t afford not to stock this particular book or series from an independent publisher.”

So what does all this mean for anyone with an idea in search of an audience? (That includes you).

It means that it’s time to go beyond what publishing used to be and start planning based on what it is now and where it’s going to be.

“It’s time to go beyond what publishing used to be and start planning based on what it is now and where it’s going to be.”

Click to tweet this.

The blockbuster sellers in hard copy aren’t going to go away. But we are going to be seeing a lot more long-tail projects get into the hands of a lot more people” and in far less time than before. Much of that is going to hinge on micropublishing and self-published ebooks.

It’s time to get serious about embracing Amazon’s publishing model and ebooks as a viable platform for mass audiences.

You’re a publisher now. You can do this.